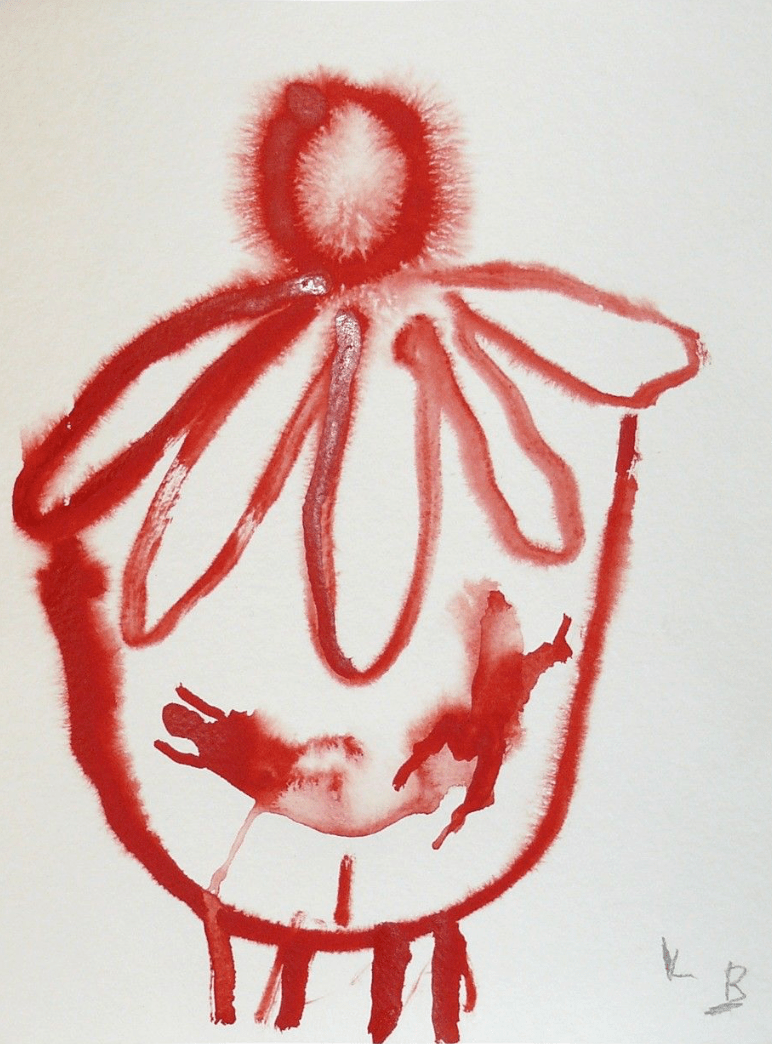

In Cabeza, Basquiat doesn’t paint a portrait—he excavates one. The head, fractured and stitched with frenetic linework, is both mask and MRI, radiating pain, power, and perception. With glaring eyes, gritted teeth, and exposed bone, the figure feels less like a person and more like a survivor of history—a psychic x-ray of Black identity in a white cultural frame.

The palette is explosive: blood-orange, gunmetal blue, surgical white. The marks are urgent—slashes, graffiti, diagrammatic gestures—combining anatomy with street vernacular, West African reliquary with subway scrawl. Language collapses into symbol: crown, fence, fragment, wound. Cabeza is not just a head—it’s a field of struggle, a site where trauma is inscribed and resistance refuses to be erased.

This is Basquiat at full voltage. No ornament. No apology. A painting that pulses with unfiltered cognition, not just expressing the self but asserting its right to exist—loud, raw, sovereign.